Researchers Use CT Scans to Monitor Long-term Brain Alterations in Sheep Models of Batten Disease

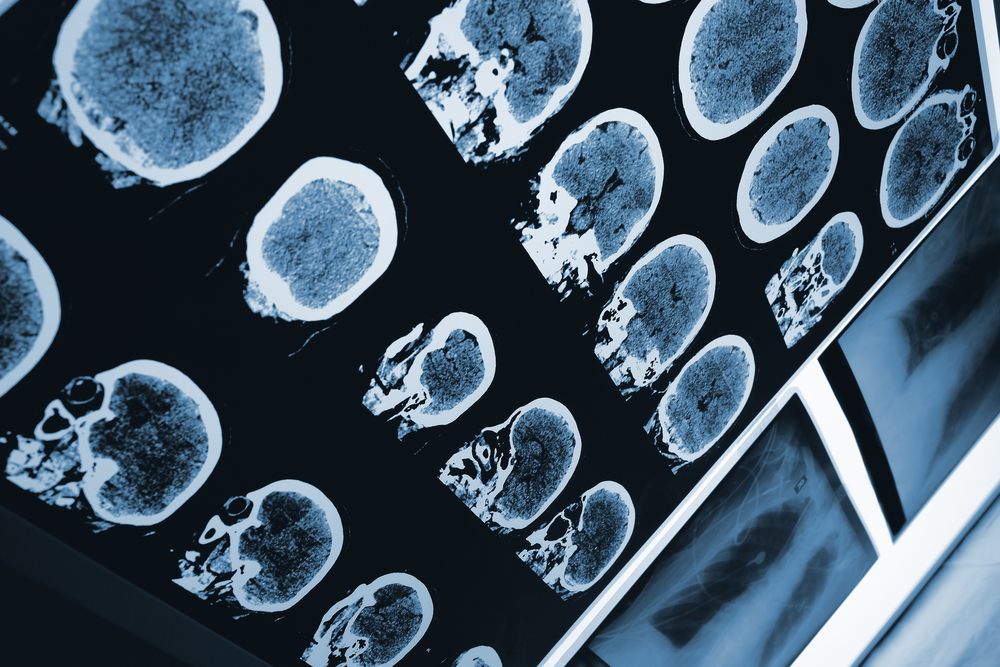

New Zealand researchers used computed tomography (CT) to measure and monitor brain alterations in sheep models of Batten disease, a study reports.

Data revealed that brain atrophy starts in specific regions of the brain, called occipital lobes, spreads to the whole cortex, and eventually leads to a severe reduction of intracranial (brain cavity) volume as the disease progresses.

The study, “Computed tomography provides enhanced techniques for longitudinal monitoring of progressive intracranial volume loss associated with regional neurodegeneration in ovine neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses,” was published in Brain and Behavior.

Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs), also known as Batten disease, comprise a group of fatal childhood neurodegenerative disorders with a wide range of symptoms, including vision loss, lack of motor coordination, and impaired cognition. Two distinct forms of Batten disease caused by mutations in the CLN5 and CLN6 genes are currently being investigated in well-established sheep models.

Post-mortem examinations of these animals has revealed that brain atrophy is accompanied by a marked thickening of the skull and a reduction of intracranial volume (ICV) — defined as the total volume within the cranium, including not only the brain, but also the meninges that protect the brain and cerebrospinal fluid.

This ICV reduction becomes more severe over the course of the disease, suggesting that ICV could be used to assess disease progression.

Ongoing gene therapy trials in these sheep models are already providing encouraging results. However, these and other translation studies require long-term follow-up of specific animals to monitor brain alterations over the course of the disease.

In this study, investigators used CT-based 3D reconstruction to evaluate and monitor ICV and brain volume alterations in sheep with NCL for a period of 19 months.

A CT scan is a computerized x-ray imaging procedure where a narrow beam of x-rays is aimed at the area of interest and produces signals that are processed by the machine’s computer to generate imaging “slices” of the body.

The longitudinal study analyzed CT scans from 56 male and female sheep, between 3.6 and 68.4 months old, including 14 healthy control animals and 42 genetically modified animals lacking CLN5 or CLN6.

Data revealed that ICV was significantly reduced in NCL-affected animals at 80.5 mL, compared with 99.9 ml in healthy control animals. Brain volume was also significantly reduced at 76.5 ml, compared with 101.1 ml in healthy control animals.

In addition, CT-based 3D reconstruction also showed that ICV tended to decrease in NCL-affected sheep as animals got older over a period of 10 months in animals deficient in either CLN5, from 89.2 ml to 78 ml, and CLN6, from 82.5 ml to 72.4 ml, unlike control animals, in which ICV actually increased from 108.3 ml to 110.1 ml.

On average, sheep lacking CLN5 lost a total ICV of 6.7 ml between three and 17 months, while the ICV of healthy control animals increased by 2.7 ml over the same period of time. Researchers found the same trend among sheep lacking the CLN6 gene, which lost a total ICV of 5.8 ml, whereas control animals gained an average of 3.8 ml.

These findings validate the use of CT-based 3D reconstruction to analyze and monitor ICV alterations in sheep models of Batten disease over long periods of time.

“The findings of this study are significant as the techniques developed here for repeated, noninvasive, measures are already being used as valuable tools for the assessment of disease progression in trials of potential new therapies for the treatment of human NCL,” the researchers concluded.