Both Rare and Classic Juvenile Batten Types Show Changes in Skeletal Muscle Cells, Study Finds

Written by |

The activation of a recycling pathway, a process called autophagy, which leads to large storage vesicles in muscle cells, is a feature of all forms of juvenile Batten disease, a small study suggests.

The study, “Autophagic vacuolar myopathy is a common feature of CLN3 disease,” was published in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs), a group of neurodegenerative disorders also known as Batten disease, are characterized by an accumulation of insoluble waste deposits called lipofuscins inside cells from several tissues, including the central nervous system and the retina.

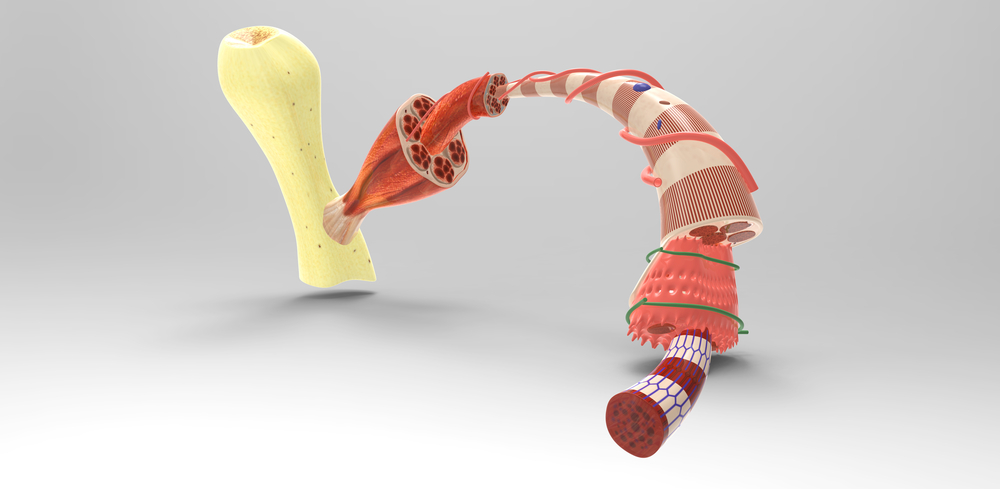

The disease is characterized by the toxic accumulation of molecules inside lysosomes — cellular structures responsible for breaking down waste molecules — which mainly affect brain cells.

Juvenile Batten disease (JNCL), the most common type of NCL, is caused by a mutation in the CLN3 gene.

Children with JNCL usually begin showing their first symptoms — progressive loss of vision, seizures, and progressive degeneration of nerve cells — between the ages of 5 and 8, and as the disease worsens, they gradually lose their ability to move and communicate, and many end up developing dementia.

JNCL may also include a rarer form of the disease, called the protracted form, characterized by a delay in the onset of typical clinical symptoms and where patients’ muscle cells develop large storage vesicles — called vacuoles — inside.

These vacuoles originate from the activation of a pathway called autophagy: cells’ own “cleaning system” to dispose of damaged materials and recycle them to make new cellular components, such as new membranes. Autophagy works closely with lysosomes to promote the degradation of the materials cells no longer need.

Researchers in this study investigated whether autophagic vacuoles could also be present in classic JNCL due to CLN3 mutations.

They analyzed skeletal muscle (the muscles under voluntary control) biopsies from three non-related patients with classic JCNL disease and one patient with the rarer, protracted form of the disease.

The patient, a male, with the rare form of JCNL disease had impaired vision by the age of 5 and, by the age of 18, was completely blind. At 11 years old, he developed generalized tonic-clonic seizures, mainly at night while he was asleep, followed by disorientation and confusion.

Now, at 34 years old, he has begun to show signs of cognitive decline and the first signs of movement disorder.

The other three patients, all males, developed the classical symptoms — rapid loss of vision — between 3 and 4 years old, followed by epilepsy, behavioral problems, and dementia.

Both muscles biopsies belonging to the three classical cases of JNCL, as well as the muscle sample from the patient with the rare form of the disease, were positive for autophagic vacuoles.

Although this was a small study, these findings suggest that the presence of autophagic vacuoles in skeletal muscle is probably a feature of general JCNL disease, and not restricted to rarer forms of the disease.

Researchers also identified a new mutation in the CLN3 gene (c.1056+34C>A) in one of the three patients with classic JNCL.

“We clearly show, that not only protracted but also classic CLN3 myopathology is not only lysosomal but also autophagic,” the researchers said. “Hence, the involvement of enhanced autophagy in muscle fibers in this lysosomal condition does not appear to be a matter of protracted or prolonged duration of CLN3 disease.”

“Our findings further illustrate that muscle biopsy in NCL may be rewarding and may help to find the correct clinical diagnosis,” they concluded.