Educational Intervention Needed Early in Batten Patients, Report Suggests

People with Batten disease would likely benefit from early educational interventions that allow them to make up for their lost eyesight and speech with alternative communication skills — even before they are actually needed — according to a report from the Juvenile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis and Education Project (2014 – 2017).

The project questioned assumptions that educational interventions are unnecessary in a patient group destined to decline, instead highlighting the idea that learning skills — making up for lost capacities — may improve the quality of life for children and young adults living with the disease.

These skills are, however, best learned before they are needed, as later implementation risks being too late, as children go into a disease stage marked by cognitive decline.

The report, titled “Aspects of Learning for Individuals with the Juvenile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (JNCL) or the CLN 3 Disease,” was a result of collaborations between institutions from Norway, Finland, Scotland, England, Germany, Denmark, and the U.S. — all part of the Education Project.

Juvenile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (JNCL), a form of Batten disease, is a slowly developing condition that takes away children’s ability to see, speak, and move. Eventually, children with Batten disease also lose their cognitive abilities, a feature the Education Project simply refers to as childhood dementia.

But while the dementia label may signal that educational interventions are unnecessary, and possibly even unethical, the project aimed to explore if interventions were possible and when the best time to deliver them is.

By asking, “What can be done despite all difficulties?”, the project managed to identify a range of potential interventions. They did so by surveying and interviewing patients’ parents and pedagogical staff.

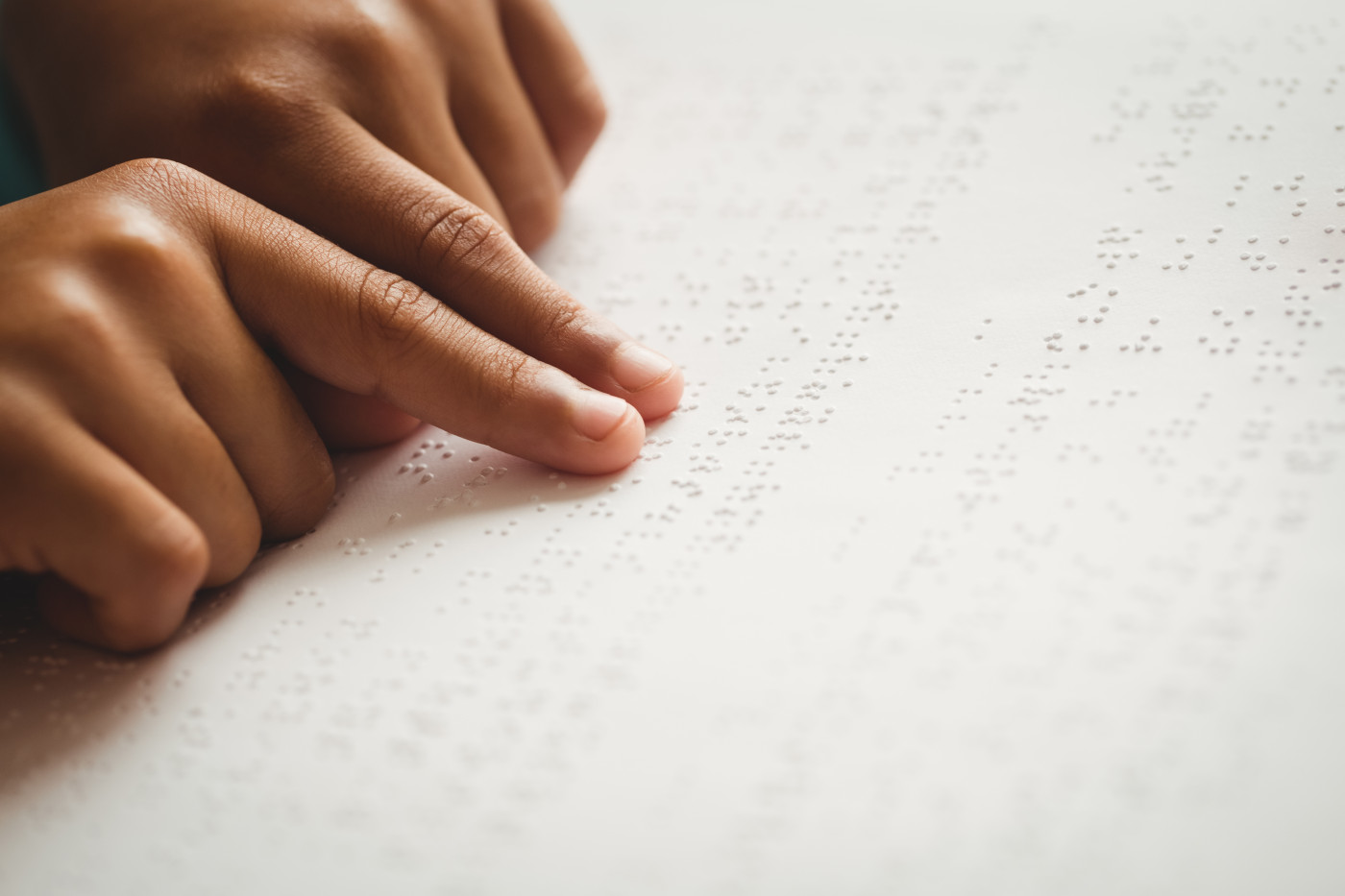

Starting out by focusing on visual impairment, their findings showed that learning braille at an early age — before children lose the ability to read and write using their eyesight — may be key to maintaining children’s ability to read and write as they grow older.

The study found no support for the idea that first learning visual reading makes learning braille easier. Instead, they noted that waiting until a child went completely blind came with the risk that increasing cognitive difficulties prevented the learning.

The project also evaluated the use of manual signs when speech became impaired. The study showed that speech comprehension was maintained throughout the disease, even when the ability to speak was lost.

Although manual signs were only evaluated in a small group of 10 children, making it difficult to evaluate if the skills persist over time, the results appear promising, the report stated. Again, it appeared that the intervention worked better if started early.

A single-person project also evaluated the transition for a young man from a student to a living situation at a resource center. The pilot study showed that with assistance, it was possible for the man to retain participation in the majority of his normal activities, and hence, maintain a good quality of life.

In conclusion, the report suggested that there are many ways to ease the burden of disabilities in children and young people with Batten disease.

Among them, learning new skills before they are needed may be key, making it possible for patients to maintain the ability to communicate and live an independent life — and hence a better quality of life.